Depression, especially in urban areas, is on the rise, now more than ever. One factor influencing mental health outcomes is the type of environment where a person lives. Former studies show that urban greenspace has a positive benefit on people experiencing mental ill health, but most of these studies used self-reported measures, which makes it difficult to compare the results and generalise conclusions on the effects of urban greenspace on mental health.

An interdisciplinary research team from UFZ, iDiv, UL, and FSU tried to improve this issue by involving an objective indicator: prescriptions of antidepressants. To find out whether a specific type of ‘everyday’ green space – street trees dotting the neighbourhood sidewalks – could positively influence mental health, they focused on the questions of how the number and type of street trees and their proximity to the home correlated with the number of antidepressants prescribed.

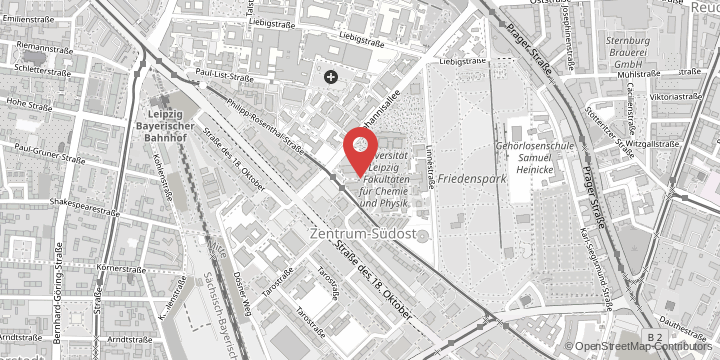

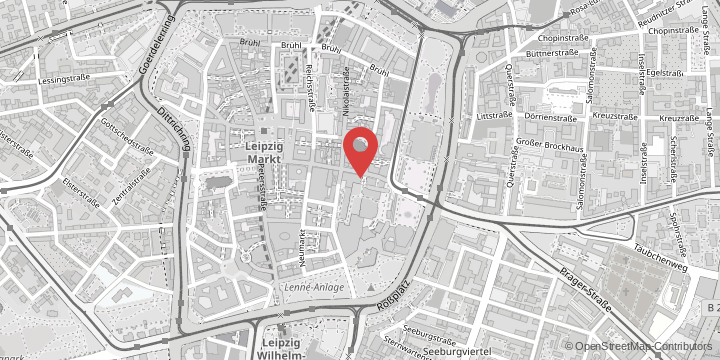

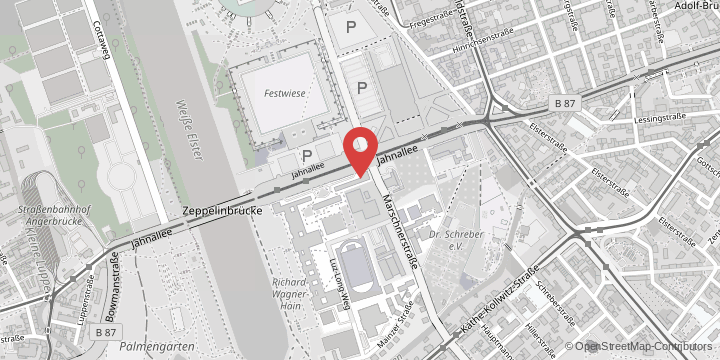

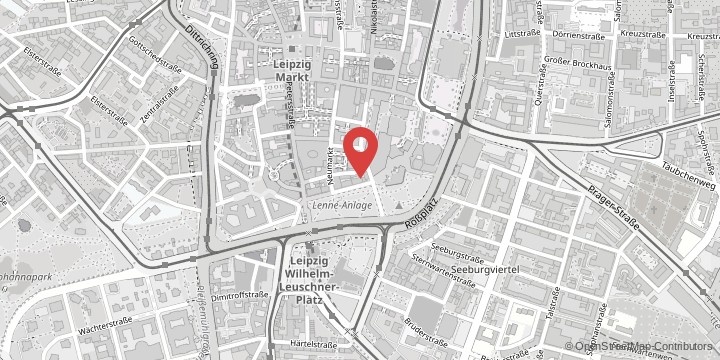

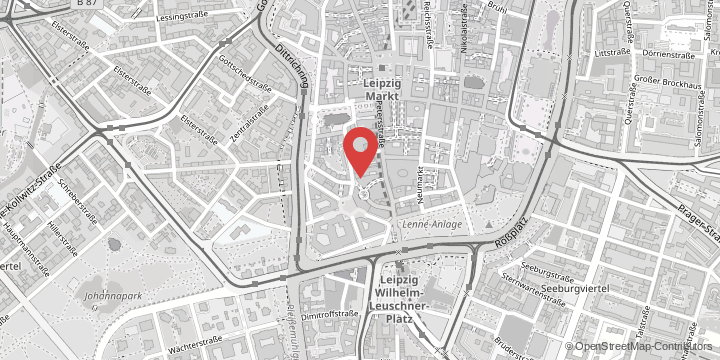

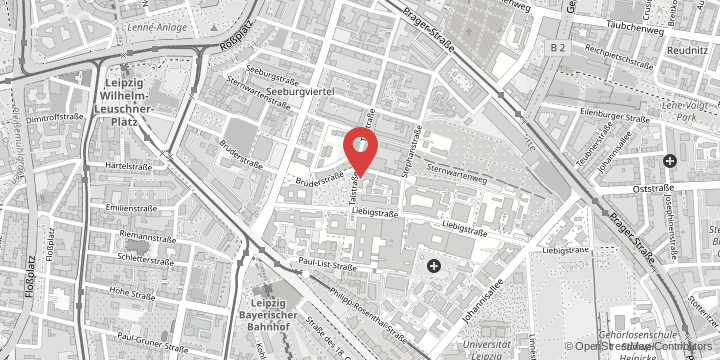

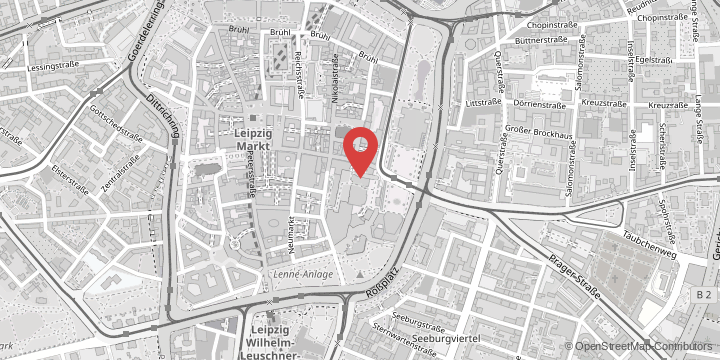

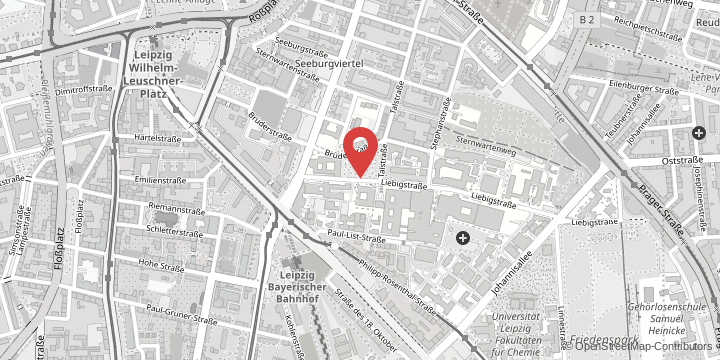

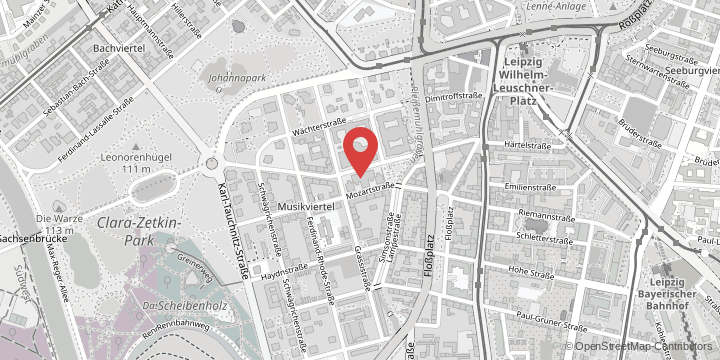

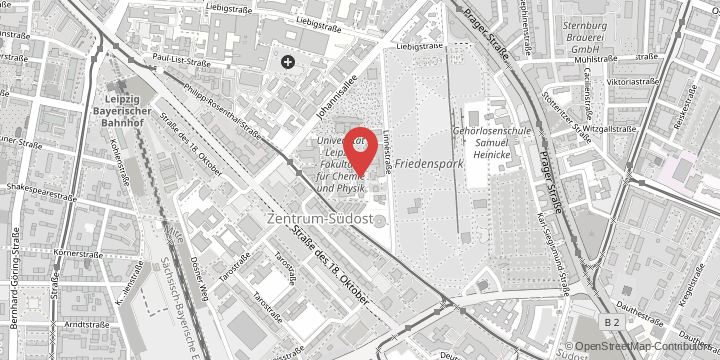

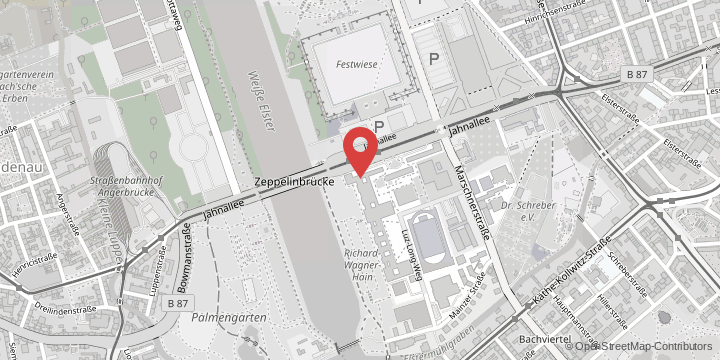

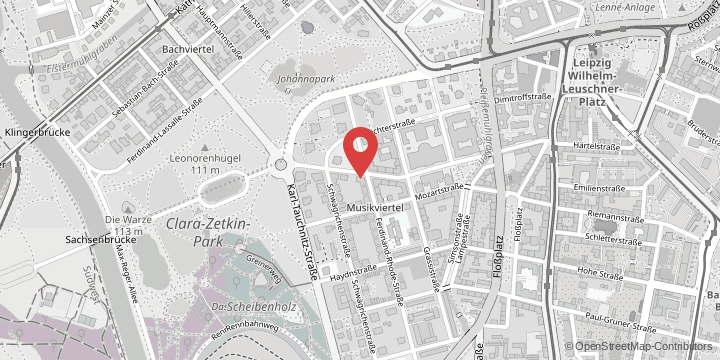

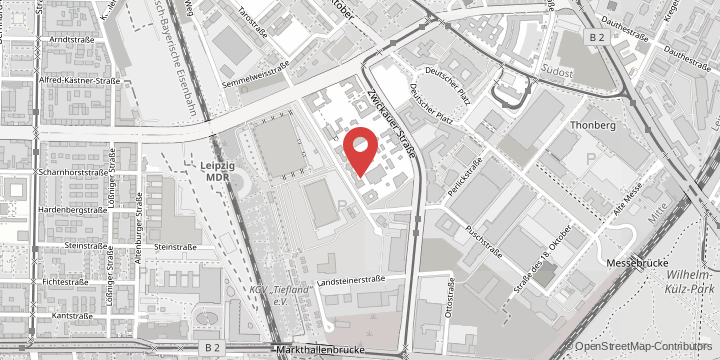

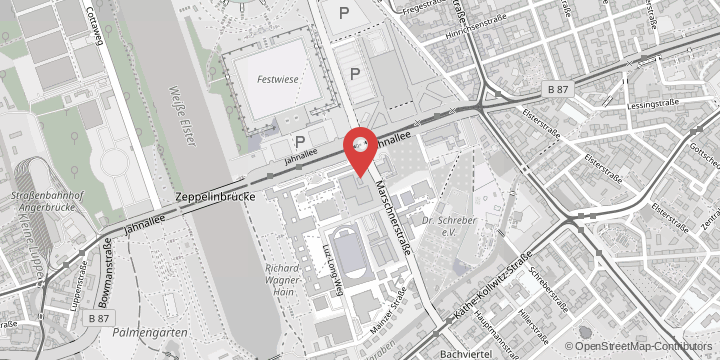

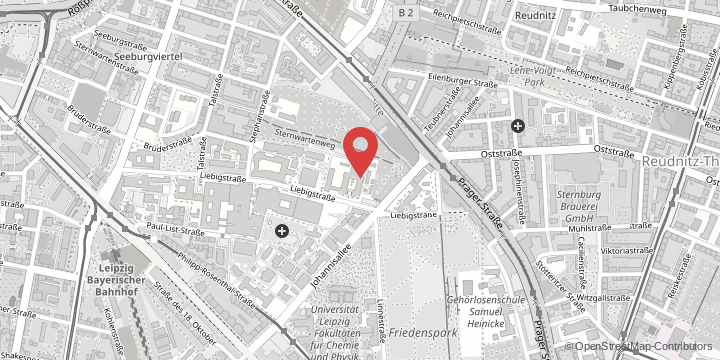

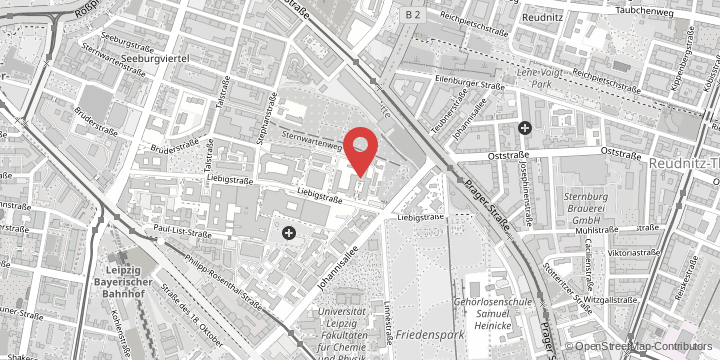

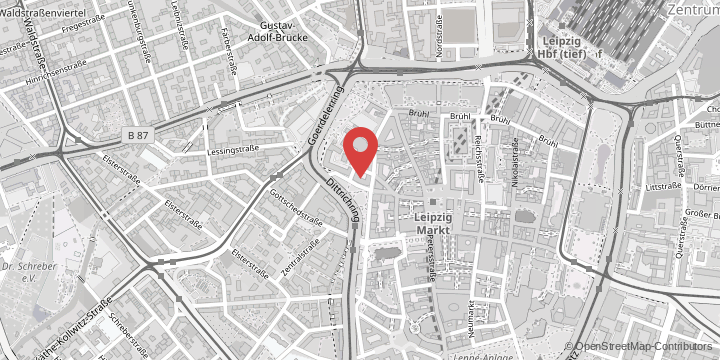

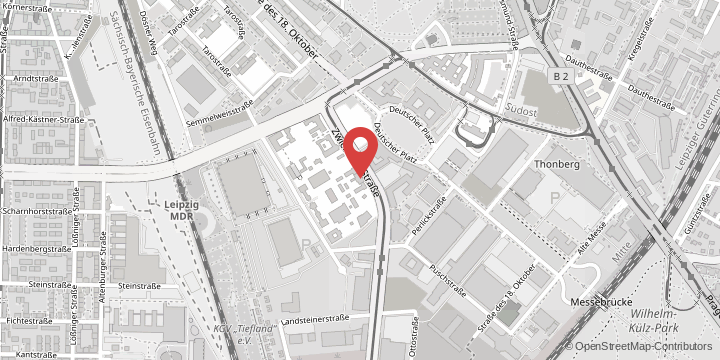

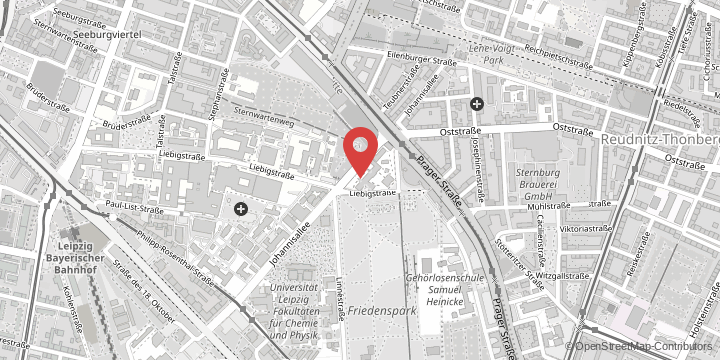

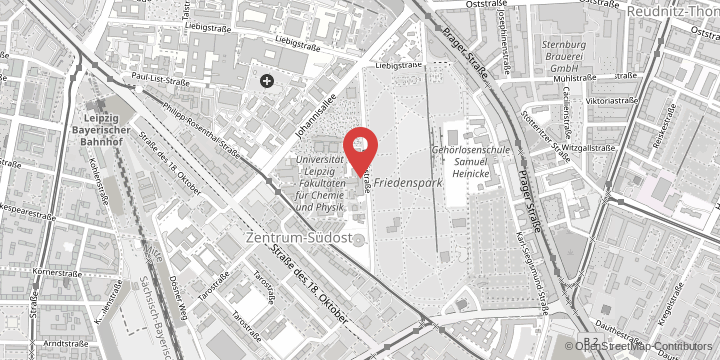

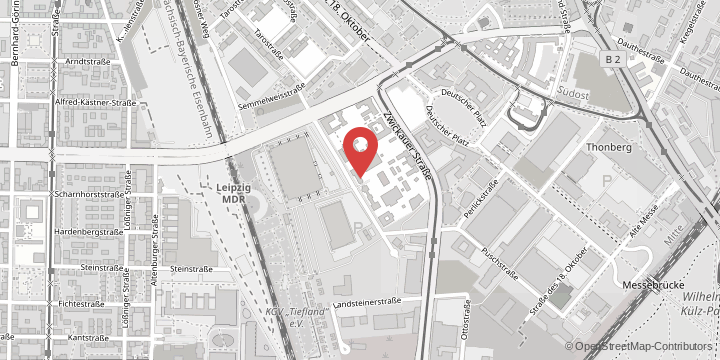

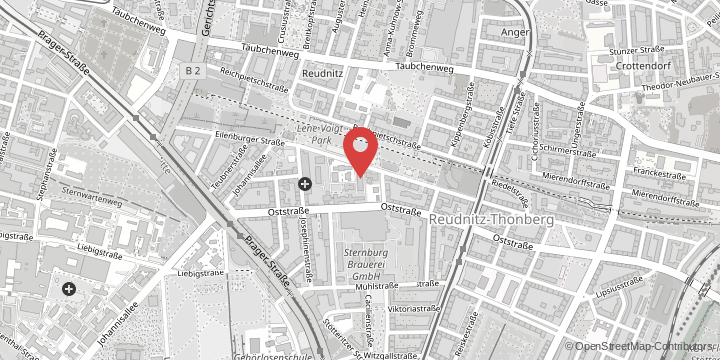

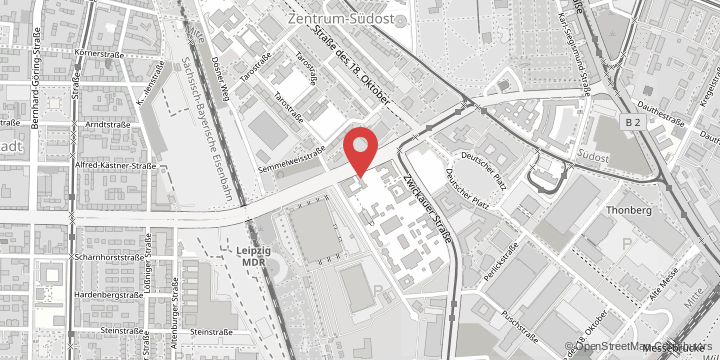

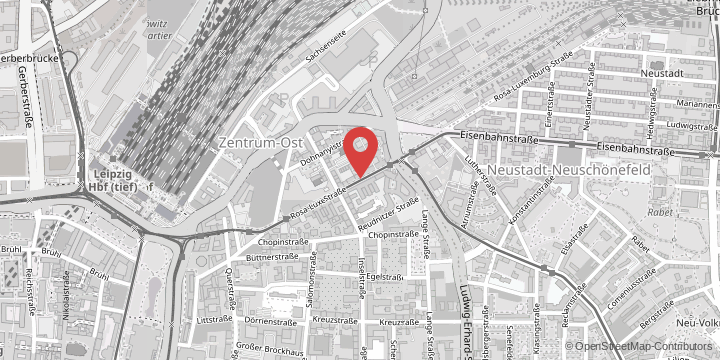

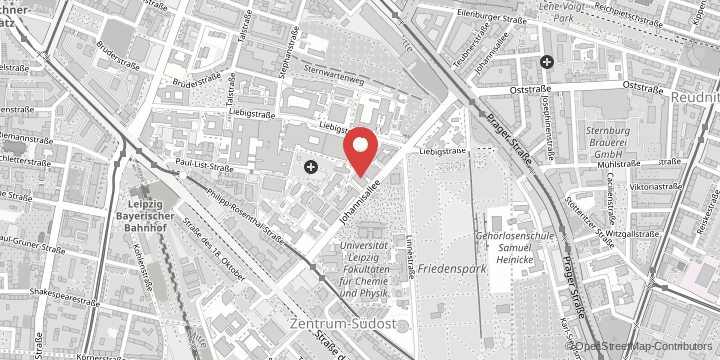

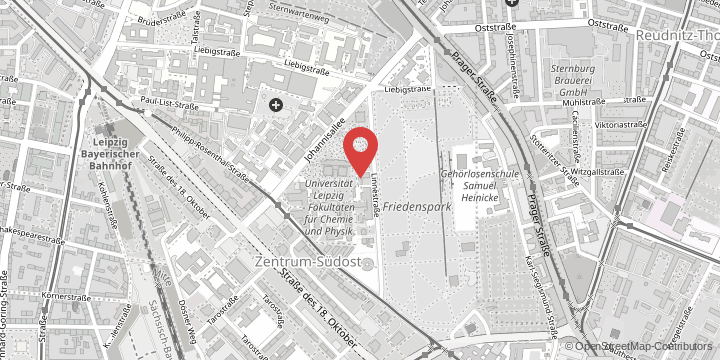

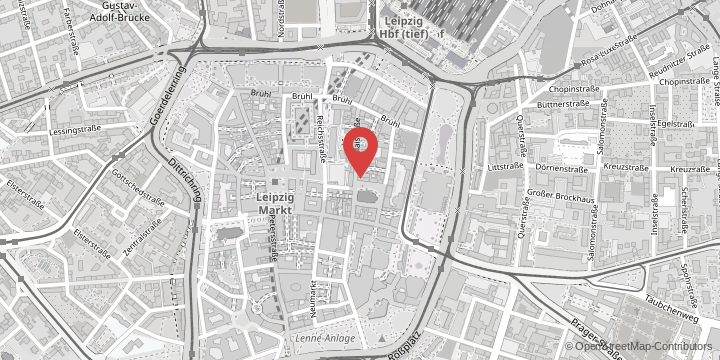

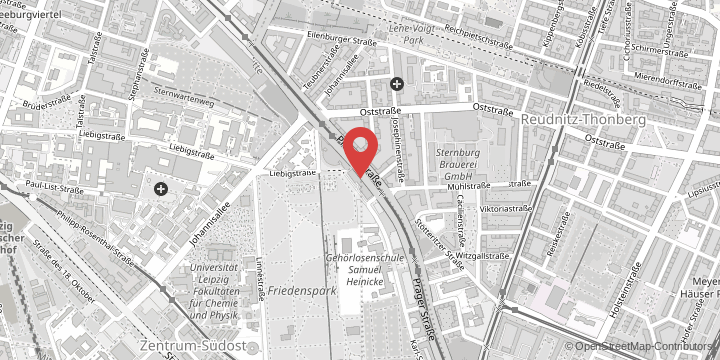

The researchers analysed data from almost 10,000 inhabitants of Leipzig, a mid-size city in Germany, who took part in the LIFE-Adult health study running at Leipzig University’s Faculty of Medicine. Combining this with data on the number and species of street trees throughout the city of Leipzig, the researchers were able to identify the association between antidepressants prescriptions and the number of street trees at different distances from people’s homes. Results were controlled for other factors known to be associated with depression, such as employment, gender, age, and body weight.

Street trees near the home may reduce the risk of depression

More trees immediately around the home (less than 100 metres) was associated with a reduced risk of being prescribed antidepressant medication. This association was especially strong for deprived groups. As these social groups are at the greatest risk of being prescribed antidepressants in Germany, street trees in cities can thereby serve as a nature-based solution for good mental health, the researchers write. At the same time, street trees may also help reduce the ‘gap’ in health inequality between economically different social groups. However, the study was unable to demonstrate any association between tree types and depression.

“Our finding suggests that street trees – a small-scale, publicly accessible form of urban greenspace – can help close the gap in health inequalities between economically different social groups,” said lead author Dr Melissa Marselle. “This is good news because street trees are relatively easy to achieve and their number can be increased without much planning effort.” An environmental psychologist, she conducted the research at UFZ and iDiv and is now based at De Montfort University in Leicester, England. Marselle hopes that the research “should prompt local councils to plant street trees to urban areas as a way to improve mental health and reduce social inequalities. Street trees should be planted equally in residential areas to ensure those who are socially disadvantaged have equal access to receive its health benefits.”

“Importantly, most planning guidance for urban greenspace is often based on purposeful visits for recreation,” said Dr Diana Bowler (iDiv, FSU, UFZ), data analyst in the team. “Our study shows that everyday nature close to home – the biodiversity you see out of the window or when walking or driving to work, school or shopping – is important for mental health.” Bowler added that this finding is especially important now in times of the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Urban tree planting can help to meet nature protection goals and social equality

And it’s not only human health which could benefit. “We propose that adding street trees in residential urban areas is a nature-based solution that may not only promote mental health, but can also contribute to climate change mitigation and biodiversity conservation,” said senior author Professor Aletta Bonn, who leads the department of ecosystem services at UFZ, iDiv and FSU. “To create these synergy effects, you don't even need large-scale expensive parks: more trees along the streets will do the trick. And that’s a relatively inexpensive measure.”

“This scientific contribution can be a foundation for city planners to save and, possibly, improve the quality of life for inhabitants, in particular in densely populated areas and in central city areas,” said Professor Toralf Kirsten from Leipzig University. “Therefore, this aspect should be taken into account when city areas are recreated and planned, despite high and increasing land cover costs. A healthy life of all living being is unaffordable.”

Original title of the publication in Scientific Reports:

“Urban street tree biodiversity and antidepressant prescriptions”, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-79924-5